A recent discovery of a stone point with a broken tip at an archaeological site in Central Texas confirms that indigenous groups were present in the area now known as Texas at least 16,000 years ago. For more on archeological discoveries in Texas, visit the Bullock Museum, which displays the stone tip in its “Becoming Texas” gallery.

For more information on Texas Tribes, visit:

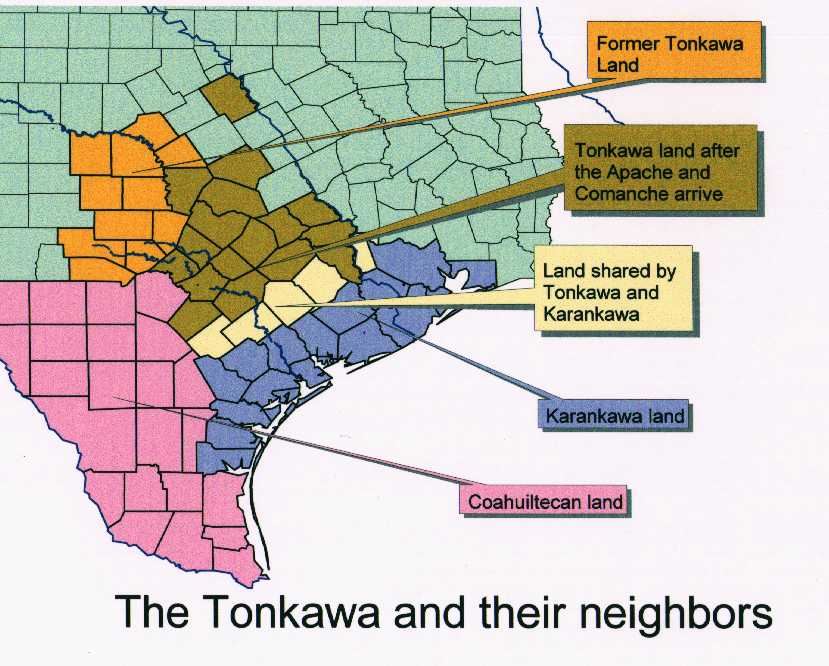

According to Deborah Lamont Newlin in The Tonkawa People: A Tribal History from Earliest Times to 1893, “The history of the Tonkawa prior to the eighteenth century is fragmental and speculative” (4). Newlin posits that the Tonkawa lived in what is now known as Texas during the fifteenth century, though the Texas Handbook claims that they actually migrated to this area during the seventeenth century.

According to Deborah Lamont Newlin in The Tonkawa People: A Tribal History from Earliest Times to 1893, “The history of the Tonkawa prior to the eighteenth century is fragmental and speculative” (4). Newlin posits that the Tonkawa lived in what is now known as Texas during the fifteenth century, though the Texas Handbook claims that they actually migrated to this area during the seventeenth century.

Deborah Lamont Newlin cites conflict with white Texans as the reason for the reservation system in Texas, as well as its ultimate failure to remain a viable option for the Tonkawa people. She writes, “The government was unable to settle successfully the Texas Indians upon an agrarian reservation mostly because of the antagonism of white Texans who insisted upon carrying out their hatred toward the Indians” (90). The current Tonkawa Tribal Reserve can be found in Kay County, Oklahoma. The tribe maintains a website called Tonkawa: The Tonkawa Tribe Official Website, where there are sections dedicated to the tribe’s history, culture, government, and current news.

The Texas State Library and Archives Commission explains the conflict on its Native American Relations in Texas site. Set off by a meeting that turned violent on March 19, 1840, The Comanche War included a series of battles occurring throughout 1840. According to the Texas State Library and Archives Commission, the war ended on October 1840, when “Colonel John H. Moore led a force into Comanche territory and attacked their village on the Red Fork of the Colorado River. Moore's troops killed about 130 warriors and took 34 prisoners. With this devastating loss, the Comanches moved away from the Texas frontier and turned their raiding attentions to Mexico.”

Unlike the other tribes who previously frequented the area that would become known as Austin, the Lipan Apache do not have their own independent reservation. The tribe continues to be led by a chairman and a tribal council, and there are currently 3,400 registered members of the tribe, as well as 8,000 unregistered family members. For more about current issues facing the Lipan Apache, visit Our Sacred History: Who We Are.