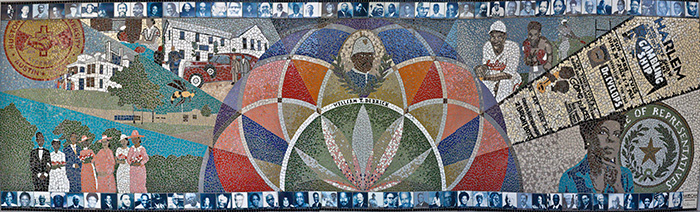

Founders

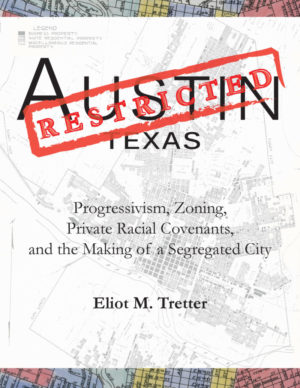

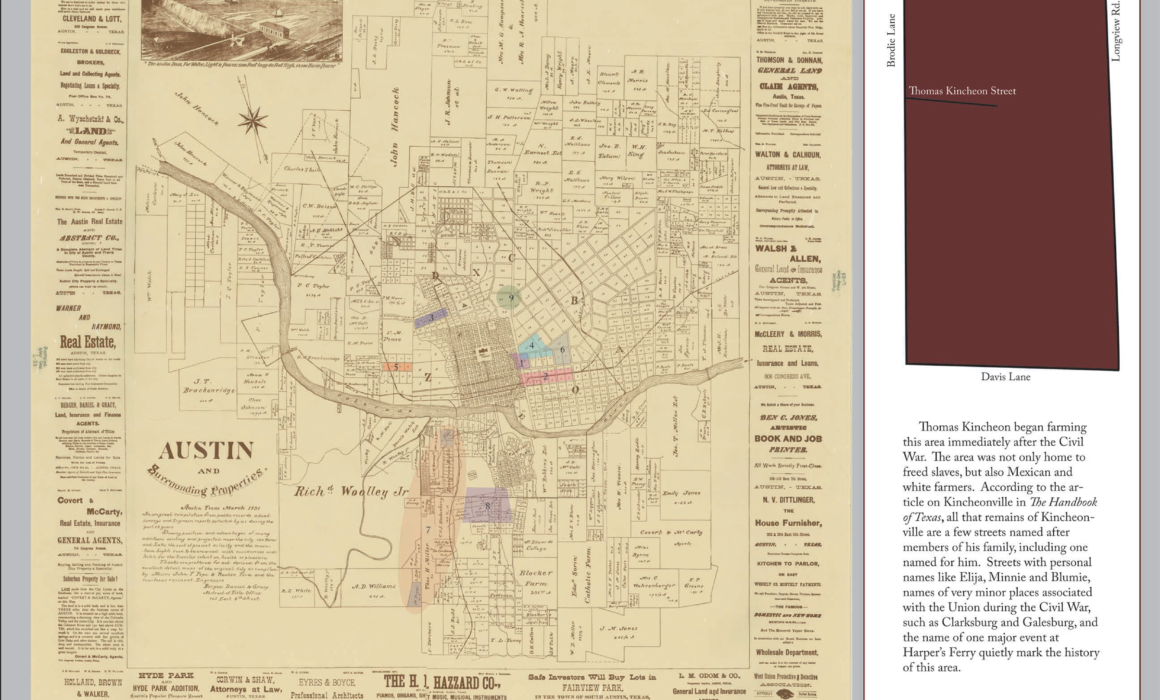

Eliot M. Tretter’s Austin Restricted: Progressivism, Zoning, Private Racial Covenants, and the Making of a Segregated City discusses the city plan and its work in conjunction with racially restrictive housing communities like Hyde Park to isolate African Americans in East Austin. The Austin American-Statesman’s “Inheriting Inequality” series provides maps to show the “Evolution of a ‘Negro District,’” and documents members of the community in “What You Don’t Know About the History of East Austin.”

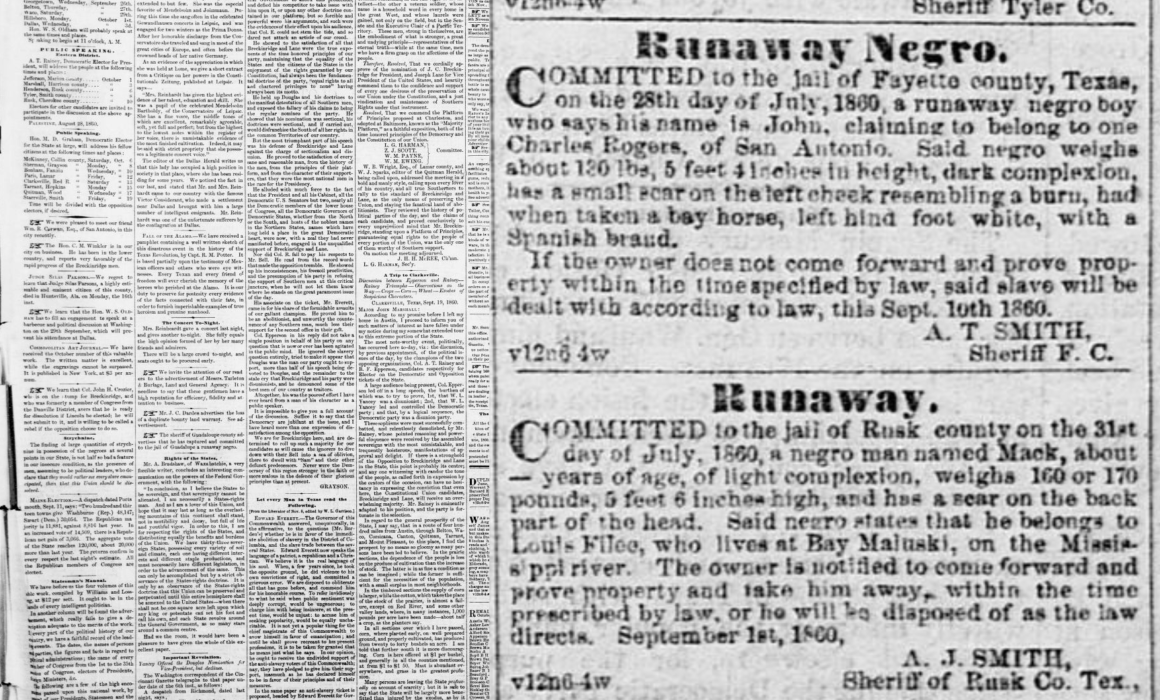

“In our studies in Austin we have found that the negroes are present in small numbers, in practically all sections of the city, excepting the area just east of East Avenue and south of the City Cemetary. This area seems to be all negro population. It is our recommendation that the nearest approach to the solution of the race segregation problem will be the recommendation of this district as the negro district; and that all the facilities and conveniences be provided the negros in this district, as an incentive to draw the negro population to this area.”

Thriving East Austin Community

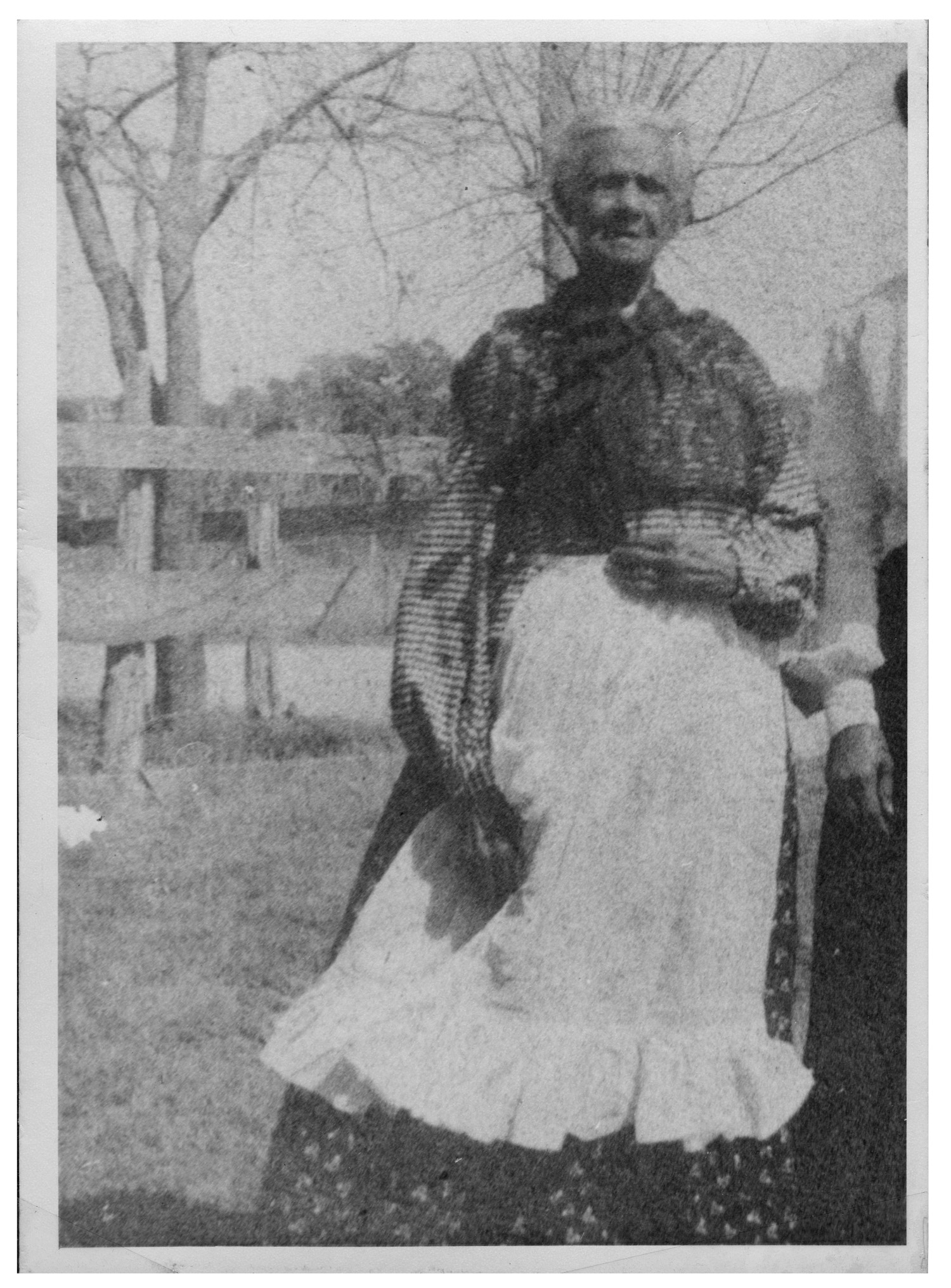

While city services remained inferior on the east side—many roads were not paved until the mid to late twentieth century, streetcar routes ended at the entrance to the neighborhood on 11th street, and segregated schools received second-hand books and resources—African Americans built a thriving community of businesses, culture, and arts. Austin’s East End Cultural Heritage District documents this community, providing descriptions of black-owned businesses and music venues in the area. Many of the buildings in the neighborhood remain important landmarks of the community, including the George Washington Carver Library, Museum, and Cultural Center. The Carver Museum includes a permanent exhibit exploring early black families living in Austin, featuring the Fontaine family, the Anderson family, and the Simond family. Sharon Hill writes about the businesses, people, and neighborhoods of this community in The Empty Stairs: The Lost History of East Austin.

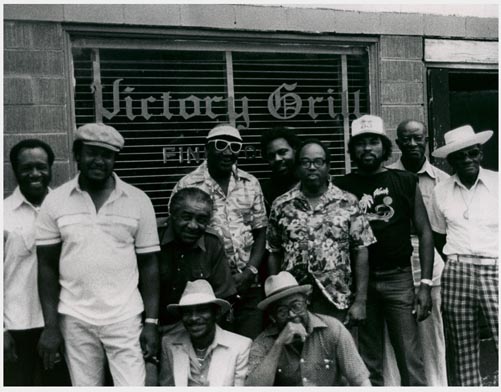

Victory Grill Reunion

(L-R Standing) Henry “Blues Boy” Hubbard, James Kirkendall, T.D. Bell, “Little Herman” Reese, William Fagan, B. Brown, Johnny Holmes, Grey Ghost, (Kneeling) Ural Dewitty and Erbie Bowser – photo by Tary Owens